Hello my fellow humans of the internet.

I've had this post on the back-burner for quite some time now, and I suddenly remembered it today as I was fiddling with some dollars at the grocery store. As our economy thunders forward and people like me lose touch with the reality of those not working in tech, I thought now would be a good time to meditate on an experiment I did back in 2016 and ground myself a little bit in my first-hand realization that poverty has some particularly subtle and insidious effects hidden in its folds.

All through my travels I had obsessed over what people spent their money on and where the money came from. At times it was a complete mystery to me how people made ends meet, yet they did, and it always made me curious to see if I could do it under the same constraints. I talked about money a lot, too, with people from all over. I would hear people from the States complain about how no one could pay rent on $8.50 per hour, and I constantly confronted my own doubt about that. I've always been cheap. I bet I could do it just fine.

So in 2016, after moving back to Chicago after two years in Panama and a couple months in Nepal, I decided to try a year on minimum wage. I was living on savings, and it made sense to be frugal. Additionally, I was trying to start The Operations Institute, a would-be non-profit management consultancy and open-source software factory, and was anticipating pouring a substantial sum into that. All this made it pretty easy to come to terms with a shoestring budget.

What I learned at the end of the year was that, yes, you can do it..... and no, it's not good for anybody. Here are a few of the most important insights from the experiment.

Risk

This is first because it was the most significant epiphany for me. This experiment really helped me quantify risk and its value for the first time, along with all the quotidian things that don't seem like risks but actually are when you're poor.

For example, let's say you do have some sort of talent you've fostered and can use to get a better paying job. If you're like 100% of other humans, the best chance you've got is through your network. But you're poor, so you probably don't have much of a network. How do you build your network? Well, through a million different ways, none of which are in any way guaranteed or even likely to get you your better job. You might try going to meetups, volunteering, blogging, striking up conversations on the bus, whatever.

But there are hidden costs in each of these networking activities. One of the most tangible examples that I can remember was the decision of whether or not to buy a nice shirt and pants to meet people in. As stupid as it sounds, I actually did stress over this more than once. What's the ROI on this? What if I have a second meeting and need another nice shirt and pants? Do I buy those, too? Or how about paying the bill for a coffee meeting with a new contact? Is that worth it?

All of it's a gamble when you're poor. Something will pay out. Maybe that contact was really impressed by your neatness and coif. Maybe they were impressed by your social grace when you casually offered to take the tab. The fact is that you can't say what will be the deciding factor, and so you either take the risk and spend money you don't have or you stay inside your budget and pay the opportunity cost instead.

Education is another good example of risk. Who knows whether you'll actually get the job you're envisioning after going through that 12-week instensive nights-and-weekends skills training? Who knows whether or not that job will actually be better than the one you've got? What if you face a medical or family emergency half-way through and are unable to finish the course? Can you really afford the risk?

The big lesson in all this for me was that most successful people have a certain amount of ongoing spend that looks casual or social or simply personal (like buying clothes that actually make you look good), but is actually essential to their continued success. It's a baseline expenditure on a "portfolio of risks," some of which will pay back, and only in ways that are usually hard to tie back to the original investment. That makes it really easy for us to accept the spending of the wealthy as normal, because, "oh, they can afford to have fun", and attack the spending of the poor as pathological, because they can't.

The Minefield of Meager Savings

Ever hear someone say, "a penny saved is a penny earned"? That was me, pre-2016, piously preaching that you can actually save yourself out of poverty. The idea was that, with a dollar here and a dollar there, you could eventually build enough capital to change your lot in life.

While in a technical sense that may be true (at least when you combine multiple generations of such meticulous saving), the fact is that the world is absolutely full of landmines that will instantly explode the result of years of austerity and sacrifice.

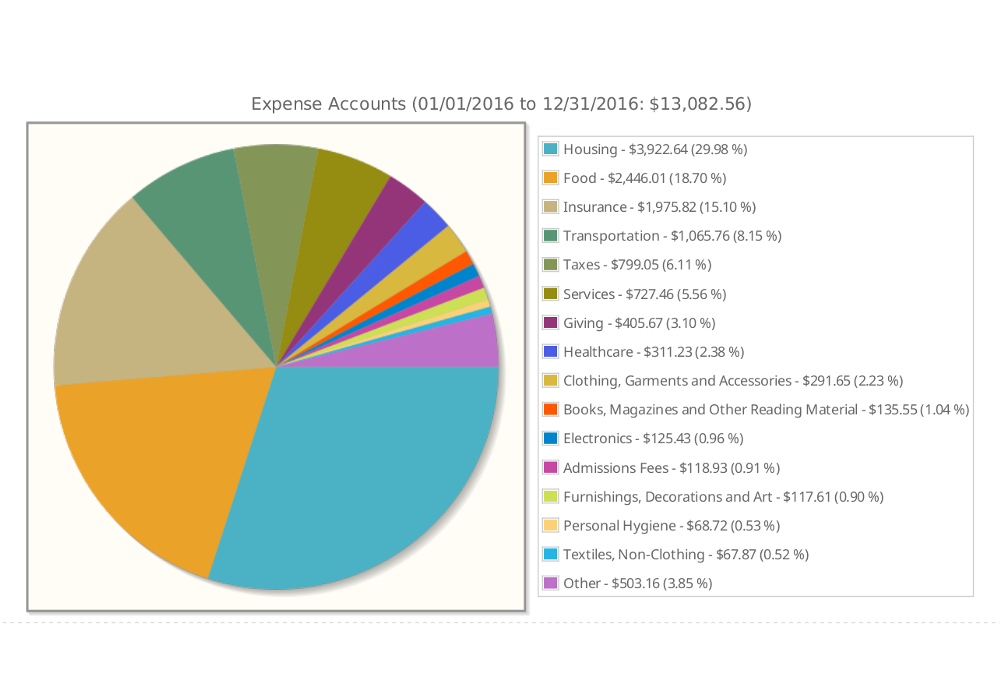

To anchor this in reality, my total spend during 2016 was $13,082.56, of which ~$11,700 (about 90%) went to the most basic living expenses, and even those expenses were unusually low. I was paying only $400 per month in rent at the time (unheard of even in the poorest parts of Chicago); I had the luxury of cooking 100% of my meals at home (also effectively unheard of for someone working at least one full-time job); I didn't own or drive a car, or even spend significantly on public transit; I suffered no significant health issues (except one, which I didn't do anything about because - of course - it wasn't in the budget).

At $13,000 total and $11,700 basic expenses, the most I could possibly have saved during that year was about $1,400, or roughly $115 per month, and that only if I bought not a single gift for anyone for Christmas, birthdays, mothers day, fathers day, or any other holiday; not a single cup of coffee; not a single meal at a restaurant of any kind; not a single trip to a museum or show; not a single night out to the movies; and if nothing happened to me. And as I argued above, at least some of these "luxuries" are not luxuries at all, but necessary investments in your social network.

Ok, so if my max potential for the year is $1,400, here's what can happen to destroy that:

- I get hit by a car while riding my bike.

- I get hit while driving my car (even just doing all the paperwork and repairs for a minor incident can wipe out several months of austere saving) (happened to a friend).

- I get a speeding ticket, which, incidentally, is way more likely in poorer parts of town.

- I get a red light ticket from one of the many red light cameras also lurking disproportionately in poorer parts of town.

- I slip and fall on ice and can't work for a few days.

- I catch a bad flu that puts me out of work for a week.

- I get a big bill from the hospital for a check-up I thought was routine and already paid for (actually happened to me).

- A good friend of mine hits hard times and needs help (and I've been there, so I help them out).

- I spill something on my only nice clothing.

- There's a major clerical error somewhere and I have to take time off work to chase down people and papers to fix it (happened to a friend).

- My identity is stolen.

- My computer dies and I need to buy a new one and recover as much as I can from the old one (happened to a friend).

- A water line breaks in my apartment and I have to miss work while I chase the landlord down to fix it and replace any of my stuff that got ruined (happened to a friend).

- My hours get cut at work for no reason (happened to a friend).

- I lose my job entirely (happened to a friend).

- I take a gamble and switch jobs requiring a few days without work during the transition (happened to a friend).

- And god forbid I have kids and anything happens to them.

The list goes on, but I think you get the point: Basically anything will stop you in your tracks when you're running on fumes.

So now when I see people spending their extra $115 per month on shoes or cell phone bills or whatever else, I'm not quite so judgemental. I'd probably give up, too, if the foreseeable future were just as god damn poor as the present. Which brings me to my next point.

Hopelessness

I think people sometimes discount hopelessness because it's technically within our power as individuals to keep a good attitude and avoid it. It takes a special kind of person, though, to get punched in the face their whole life and still love the world they live in.

Hopelessness is a real dimension of poverty, and it's something I think we need to look at when we talk about beating poverty. On top of all the concrete things like not saving money, not seeking opportunities, and possibly getting addicted to drugs and/or alcohol, a person who's hopeless is also not going to bring that touch of inspiration that could make the difference in their next job or promotion opportunity. We look at people and say, "come on, stand up, how could you let yourself get beaten down?" but we don't look at a boxer facing impossible odds and say, "come on, take one more hit to the head and maybe something will get better." Why is it that we have so little sympathy for real people who need real help?

In my case, I never got hopeless because I still had money in the bank, and I was still confident I had good employment opportunities available. The constraints on my life, however, were sufficient to make me feel that cold frost on the horizon. Life is just not fun in poverty, and when you think of all the reasons you have to keep on living, very few of them involve the joy you get from watching your meager savings grow in tiny fractions month to month, only to periodically be wiped out by random occurences outside your control.

More likely you're thinking of things like spending time with your kids, hosting dinner for your family and friends, giving the perfect gift, volunteering for your community, enjoying great food or wine or beer, learning new things, doing something creative....

None of which you can do when you're living on minimum wage. And so the question arises.... why keep on living? And is that really a question we want our fellow humans to be asking?

My experiment was just that: a specific period in time during which I placed artificial constraints on my life. It was interesting, but it wasn't real. It's real to millions of people across our nation and the world, though, and even dipping my feet in was enough to humble me.

This experience was really invaluable for me. It absolutely changed my perspective on poverty and how I think of people who are struggling with financial problems. And yes, there are certainly people who could pare down some, and there are also a few bad people in the world who really are just frivolously overspending money that was never theirs to begin with, squandering opportunities and common resources, and ruining the image of others not so callous. But that's far from the norm.

Poverty is quiet and often barely visible. You see it only when you go to where it is. You understand it only when it touches you personally. It hides from the people who can do something about it, and it terrorizes and often kills those who can't.

So now for the practical solutions, right? Unfortunately, no. As most people understand by now, poverty not a simple problem, and (obviously) there are no simple solutions.

If you're in a position to help, perhaps the best thing you can do is go to it. Find poverty and see it. Find the poor side of your town and make yourself available and accessible for friendship and collaboration. Get to know people there and go spend time with them. Look for community events - block parties, talent shows, fundraisers, concerts, whatever - and show up. But don't forget your humble hat! It won't help if you walk in like you're there to save everybody. I've found it works best to enter these spaces as if you're a guest being allowed to participate.

And if you're on the other side, then find ways to bring people into your communities from outside. Be the one who puts on the talent show or block party, and make sure people from outside the community get an invite.

In the end, it's humans that make the difference in other humans' lives. In our modern era, we attempt to use the government as a proxy for our own efforts and care, but it hasn't worked and I don't think it will ever work. The government is not what people living in poverty need. They need good friends and neighbors - a broad network with a lot of statistical possibility. They need to capitalize on connections and the natural generosity that's only unlocked when individuals get to know each other. They need people who expect them to succeed and who are willing to invest in however small a way when they see the glimmer of hope light up in a person's eyes.

So go make a new friend. Ask for help if you need it, and if you don't, then be ready to say yes when you find someone who does.